By Michel Rose and Mathieu Rosemain

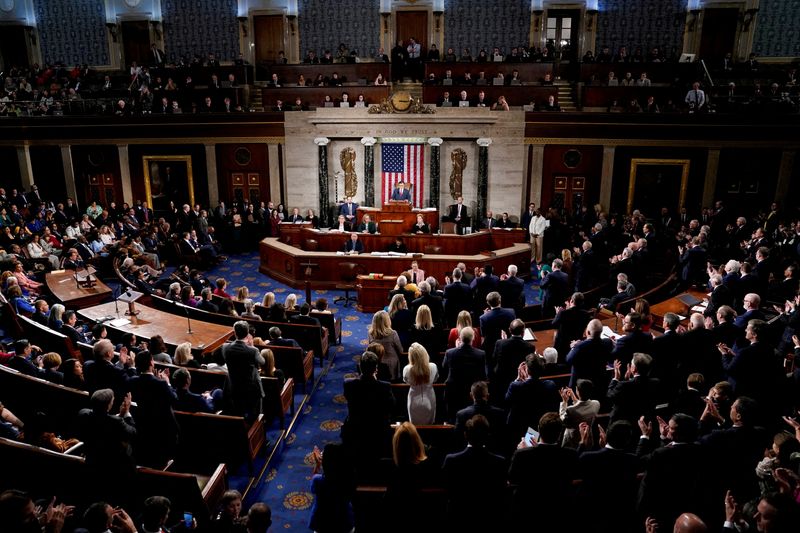

PARIS (Reuters) -France unveiled a new government on Saturday that aims to strike a fine balance between right-wingers and centrists, as Prime Minister Michel Barnier hopes to break political deadlock following snap elections that delivered a hung parliament.

After 2-1/2 months of political uncertainty since centrist President Emmanuel Macron’s surprise decision to call early elections, Barnier has put together a cabinet he hopes will find cross-party support in the fragmented parliament.

With few political heavyweights, his team includes one of the leaders of the conservative party of former President Nicolas Sarkozy, Bruno Retailleau, who negotiated the coveted interior ministry as the price for support in parliament.

However, showing the government’s fragility, the prestigious job of finance minister was given to a little-known 33 year-old, Antoine Armand of Macron’s party, having been turned down by more senior politicians.

The public finances portfolios, shared with new budget minister Laurent Saint-Martin, will have the unenviable task of putting together a budget bill before January, at a time France is struggling to contain a spiralling budget deficit.

“We must cut public spending and make it more efficient,” Armand told the Journal du Dimanche newspaper in an interview published on Saturday. “If the solution was to raise taxes, France would have long been the world’s top superpower.”

‘CONCESSIONS AND MANOEUVRING’

But despite the entry of 10 politicians from Barnier’s conservative Republicans (LR) party in cabinet, Macron kept a number of outgoing ministers in key posts. Only one left-wing politician joined cabinet, Didier Migaud as justice minister.

Jean-Noel Barrot, the outgoing Europe minister, was promoted to foreign minister.

Sebastien Lecornu will stay on as defence minister.

Macron named Barnier, the European Union’s former Brexit negotiator and a 73-year-old veteran politician, as prime minister earlier this month, but the lengthy talks he had to lead to pull together a team were an illustration of the tough tasks ahead.

The centrist and conservative parties managed to join forces, but will depend on others, and in particular Marine Le Pen’s far right National Rally (RN), to stay in power and get bills adopted by a very fractured parliament.

“The centrist government is de facto a minority administration,” Eurointelligence analysts said in a note. Its ministers “will not only have to agree amongst each other but also will need votes from opposition parties for its bills to pass in the assembly. This means offering even more concessions and manoeuvring.”

The RN gave tacit support to Barnier’s premiership, but reserved the right to back out at any point if its concerns over immigration, security and other issues were not met.

“I’m angry to see a government that looks set to recycle all the election losers,” Mathilde Panot, who leads the hard-left LFI group of lawmakers, told TF1 television.